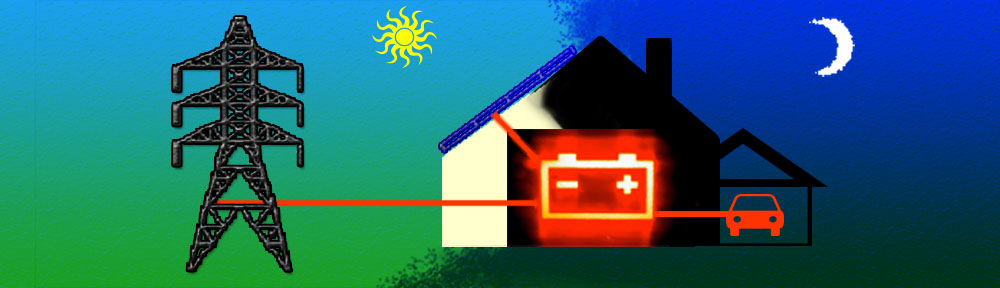

Given my evident enthusiasm for all things V2x, regular readers may be wondering why I have been more hesitant than most commentators to unequivocally applaud Greg Jackson’s announcement of Octopus Energy’s “Power Pack” retail vehicle-to-grid offer last week? £299 per month which covers all your electric mobility needs including “fuel”. What’s not to like? Surely it’s “a compelling consumer offer”, as I myself put it!

As already hinted at in my introductory article linked to above, perhaps it’s not quite so attractive if you are in fact a “prosumer”, with a few solar PV panels already installed on your very own roof? Here are some other recent items of news to ponder too. In these troubled times hackers are hard at work around the world. There was initial speculation that the recent Spanish “blackout” was a cyber attack. However, according to the BBC on April 29th:

The Spanish grid operator has ruled out a cyber attack as the cause of a massive power cut that crippled Spain, Portugal and parts of France on Monday.

Red Eléctrica’s operations director Eduardo Prieto said preliminary findings suggest “there was no kind of interference in the control systems” to imply an attack, echoing Portuguese Prime Minister Luís Montenegro the day before.

But the exact reason behind the cut is still unclear.

More recently, it was announced on June 17th that:

In January 2025, we participated in Pwn2Own Automotive with multiple targets. One of them was the Tesla Wall Connector — the home charger for electric vehicles (including non-Tesla ones)…

This article explains how we studied the device, how we built a Tesla car simulator to communicate with the charger, and how we exploited this logic bug during the competition.

The “hackers” of the Tesla wallbox wore “white hats”, but what might have happened if they had been wearing “black hats” instead? While you ponder your answer to that question, you may find it reassuring that the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre has been worrying about it for quite some time. According to the NCSC’s web site their mission is:

Making the UK the safest place to live and work online.

We support the most critical organisations in the UK, the wider public sector, industry, SMEs as well as the general public. When incidents do occur, we provide effective incident response to minimise harm to the UK, help with recovery, and learn lessons for the future.

The first example use case for their efforts reads:

Defending the digital infrastructure on which a sustainable world depends.

For example, by helping to protect a flexible energy system from cyber threats.

In November 2023 the NCSC published a blog post that began as follows:

In 2020, the NCSC published a white paper on Preparing for Quantum-Safe Cryptography. This paper explained the threat that a possible future quantum computer – one much larger, and much more capable, than any that exist today – would pose to a large class of widely deployed cryptography. That cryptography is known as public-key cryptography (PKC). PKC is the enabling technology for secure communication at scale, on the internet and many other networks.

The same white paper also explains why NCSC’s recommended mitigation of the quantum computing threat is quantum-safe cryptography, or post-quantum cryptography (PQC). PQC is cryptography that is resistant to attack by quantum computers, and also to today’s digital, or classical, computers. Furthermore, PQC offers broadly equivalent functionality to the quantum-vulnerable PKC currently in use, and can be deployed in many of today’s devices (including PCs, smartphones etc.) with a software update.

This seems like a simple solution to the threat from a potentially disruptive technology. And conceptually, it is – but the migration to PQC is a very complicated undertaking. This blog explains why.

Do you suppose that Greg and/or the Octopus Power Pack team have read it?