In a much anticipated announcement last week Elon Musk told the world that Tesla Motors now had a sister business entitled “Tesla Energy” which would start delivering a new product called the Powerwall later this year. Here’s a video of Mr. Musk’s presentation:

Note that at around 2 minutes 25 seconds Elon points out that:

We have this handy fusion reactor in the sky called the Sun. You don’t have to do anything, it just works. It shows up every day and produces ridiculous amounts of power. Now a lot of people aren’t clear on how much surface area is needed to generate enough power to completely get the United States off of fossil fuels….

It’s really not much, and most of that area is going to be on rooftops. You won’t need to disturb land. You won’t need to find new areas. It’s mostly going to be on the roofs of existing homes and buildings.

Now the obvious problem with solar power is that the sun does not shine at night. This problem needs to be solved! we need to store the energy that is generated during the day so that we can use it at night.

I recommend watching the whole show, but if you’re the impatient sort then skip to 11 minutes 40 seconds and listen to this bit:

What about something that scales to much, much larger levels? For that we have something else. We have the Powerpack. The Tesla Powerpack is designed to scale infinitely. You can literally make this into a GWh solution. We already have one utility that wants to do a 250 MWh installation.

According to the Tesla Energy launch press pack:

Tesla is not just an automotive company, it’s an energy innovation company. Tesla Energy is a critical step in this mission to enable zero emission power generation.

With Tesla Energy, Tesla is amplifying its efforts to accelerate the move away from fossil fuels to a sustainable energy future with Tesla batteries, enabling homes, business, and utilities to store sustainable and renewable energy to manage power demand, provide backup power and increase grid resilience.

Tesla is already working with utilities and other renewable power partners around the world to deploy storage on the grid to improve resiliency and cleanliness of the grid as a whole.

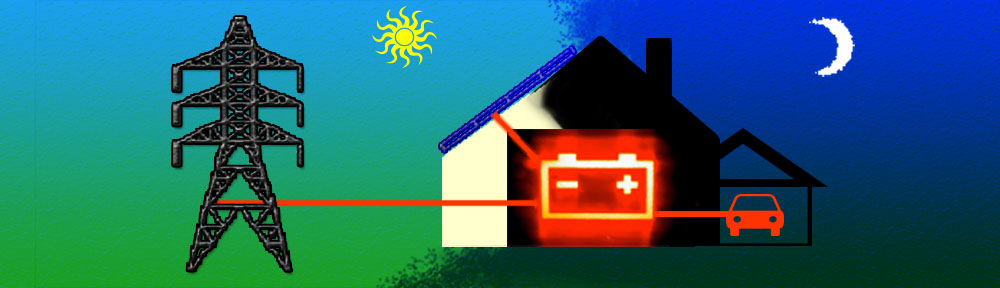

Here’s a picture of the combination of Tesla’s two businesses:

and here’s their description of the Powerwall:

Tesla Powerwall is a rechargeable lithium-ion battery designed to store energy at a residential level for load shifting, backup power and self-consumption of solar power generation. Powerwall consists of Tesla’s lithium-ion battery pack, liquid thermal control system and software that receives dispatch commands from a solar inverter. The unit mounts seamlessly on a wall and is integrated with the local grid to harness excess power and give customers the flexibility to draw energy from their own reserve.

The battery can provide a number of different benefits to the customer including:

- Load shifting – The battery can provide financial savings to its owner by charging during low rate periods when demand for electricity is lower and discharging during more expensive rate periods when electricity demand is higher

- Increasing self-consumption of solar power generation – The battery can store surplus solar energy not used at the time it is generated and use that energy later when the sun is not shining

- Back-up power – Assures power in the event of an outage

Powerwall increases the capacity for a household’s solar consumption, while also offering backup functionality during grid outages.

Powerwall is available in 10kWh, optimized for backup applications or 7kWh optimized for daily use applications. Both can be connected with solar or grid and both can provide backup power. The 10kWh Powerwall is optimized to provide backup when the grid goes down, providing power for your home when you need it most. When paired with solar power, the 7kWh Powerwall can be used in daily cycling to extend the environmental and cost benefits of solar into the night when sunlight is unavailable.

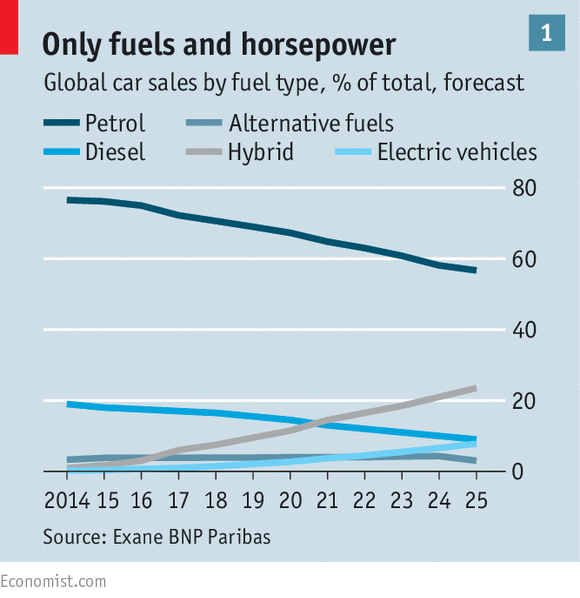

Since we are big fans of distributed energy storage here at V2G UK this is all music to our ears, but some things are strangely lacking from Tesla’s publicity. Apparently:

Tesla’s selling price to installers is $3500 for 10kWh and $3000 for 7kWh. (Price excludes inverter and installation.) Deliveries begin in late Summer.

It looks as though inverters to attach to Powerwalls will be supplied by third parties and the pretty picture above notwithstanding connecting a Tesla Model S to one or more Powerwalls and thence to the local electricity distribution grid is a problem that has yet to be addressed by Tesla themselves.

There have been some associated press releases, such as this one from SolarEdge:

SolarEdge Technologies, Inc., a global leader in PV inverters, power optimizers, and module-level monitoring services, announced its collaboration with Tesla Motors to provide an inverter solution that will allow for grid and photovoltaic integration with Tesla’s home battery solution, the Powerwall.

The joint development by SolarEdge and Tesla builds on SolarEdge’s DC optimized inverter solution and Tesla’s automotive-grade energy storage technology to enable more cost-effective residential solar generation, storage, and consumption for the global market.

Designed to manage both functions with just one SolarEdge DC optimized inverter, the solution will allow for outdoor installation and will include remote monitoring and troubleshooting to keep operations and maintenance costs low. The solution will also support upgrading existing SolarEdge systems with the storage solution.

The SolarEdge solution is expected to be available by the end of 2015.

Once again, however, whilst the phrase “grid integration” is mentioned “vehicle to grid” is not. I cannot help but wonder when (and how) it will become possible for a Model S to earn its proud owner a modest income by feeding some of the energy stored in its battery pack back into the local grid at its times of greatest need.